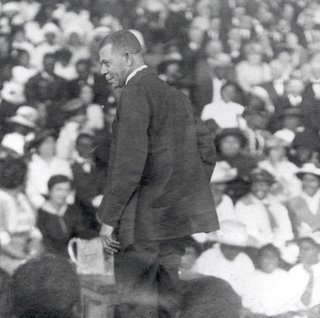

Atlanta Exposition Speech Pt. 3

We have looked at two segments of Booker T. Washington's most famous address at the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition. In this next segment of the speech we find the most controversial portion of that address. Based upon one sentence misunderstood and taken out of context W.E.B. DuBois renamed the address the Atlanta Compromise. I hope to put to rest any thought of compromise in this address and hope to shame those so-called scholars and publishers of alleged historical sites into giving the address it's proper name once again. To their credit even Wikipedia correctly names the address, while stating that it has been called by some The Atlanta Compromise.

To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth

and strange tongue and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted

I would repeat what I say to my own race, “Cast down your bucket where you

are.” Cast it down among the eight millions of Negroes whose habits you know,

whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved treacherous

meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people

who have, without strikes and labour wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests,

builded your railroads and cities, and brought forth treasures from the bowels of

the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the

progress of the South. Casting down your bucket among my people, helping and

encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds, and to education of head,

hand, and heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom

the waste places in your fields, and run your factories. While doing this, you can

be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded

by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people that the world

has seen. As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children,

watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them

with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we

shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay

down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours, interlacing our industrial, commercial,

civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both

races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers,

yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.

In this portion of the address Dr. Washington states the case for white southerners to look to the former slaves for their work force and to help rebuild the south. He reminds those southern whites that it was the Negro who looked after them, often raised their young and were entrusted with their very lives. He contrasted the ex-slaves with Europeans immigrants who were taking the jobs and creating problems via "strikes and labor wars." He reminded them that their beautiful land, railways, even cities were cultivated and built with "Black" labor. So why would you now look elsewhere. The case is made in the most passionate way reminding those southern white folks that black Americans were more than just workers and had proven themselves trustworthy and competent to "interlace" their lives with them.

In that last sentence it is clear that Dr. Washington was not opposed to integration and even encouraged it in business and private life. Only those who are too unlearned to interpret literature and those who purposely distort the written word for their own profit would not understand the meaning of this portion of the text.

The final sentence of this portion of the address is what has caused a great and lasting controversy and caused W.E.B. DuBois to dub the address the Atlanta Compromise. In it Dr. Washington stated the following:

In all things that are purely social we can be

as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand

in all things essential to mutual progress.

Let us carefully examine just what Dr. Washington said, and not what we have been told he said. I will divide the sentence into 2 parts, as he did. 1) In all things purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers. Purely social would mean social interaction such as where we live, whom we spend out recreational time with and any other social event. Booker T. Washington did not believe that social interaction was necessary to the progress of Negro society. In fact he felt it could actually hinder such progress because it was a distraction from the more important issues facing the race. This is made clear n the second part of the sentence. 2) yet ONE as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress. I believe Dr. Washington was borrowing from scripture in this statement. (Romans 12:4)

Again, I say that rather than speaking of a divided nation, he believed in a united nation but that being one which could only come about from a unified focus on the things that benefited America a one nation under God. These essentials were and are faith, law, education and a national defense. He had just alluded to the fact that we had already interlaced our lives in these areas. There was no compromise, there was no accommodation here. It was pure fact.

The following portion of the address expresses in pretty stark terms that Dr. Washington was not overlooking white responsibility toward the Black community. He gave a dire warning and even a prophetic word of what the consequences of neglecting black Americans would be.

| There is no defense or security for any of us except in the highest intelligence and development of all. If anywhere there are efforts tending to curtail the fullest growth of the Negro, let these efforts be turned into stimulating, encouraging, and making him the most useful and intelligent citizen. Effort or means so invested will pay a thousand per cent. interest. These efforts will be twice blessed—“blessing him that gives and him that takes.” | |||||||||

There is no escape through law of man or God from the inevitable:—

| |||||||||

| Nearly sixteen millions of hands will aid you in pulling the load upward, or they will pull against you the load downward. We shall constitute one-third and more of the ignorance and crime of the South, or one-third its intelligence and progress; we shall contribute one-third to the business and industrial prosperity of the South, or we shall prove a veritable body of death, stagnating, depressing, retarding every effort to advance the body politic. |

Here he urged that everything within the power of those who had it be directed at developing all Americans, and especially at this time the Negro. He believed that education was the key, but not education in the sense we are led to believe we need today. The education Dr, Washington spoke of was the education of the "Whole Man." This involved history, culture, politics and economics. These were the "things essential to mutual progress," spoken of earlier. Note the eerie prophetic warning at the end of this segment of the speech. Do this and get this, do that and get that. Sadly, it appears that they did "that" and we now have "that".

Gentlemen of the Exposition, as we present to you our humble effort at an exhibition of our progress, you must not expect overmuch. Starting thirty years ago with ownership here and there in a few quilts and pumpkins and chickens (gathered from miscellaneous sources), remember the path that has led from these to the inventions and production of agricultural implements, buggies, steam-engines, newspapers, books, statuary, carving, paintings, the management of drug-stores and banks, has not been trodden without contact with thorns and thistles. While we take pride in what we exhibit as a result of our independent efforts, we do not for a moment forget that our part in this exhibition would fall far short of your expectations but for the constant help that has come to our educational life, not only from the Southern states, but especially from Northern philanthropists, who have made their gifts a constant stream of blessing and encouragement.

Gentlemen of the Exposition, as we present to you our humble effort

at an exhibition of our progress, you must not expect overmuch. Starting

thirty years ago with ownership here and there in a few quilts and pumpkins

and chickens (gathered from miscellaneous sources), remember the path

that has led from these to the inventions and production of agricultural

implements, buggies, steam-engines, newspapers, books, statuary, carving,

paintings, the management of drug-stores and banks, has not been trodden

without contact with thorns and thistles. While we take pride in what we

exhibit as a result of our independent efforts, we do not for a moment forget

that our part in this exhibition would fall far short of your expectations but

for the constant help that has come to our educational life, not only from the

Southern states, but especially from Northern philanthropists, who have made

their gifts a constant stream of blessing and encouragement.

Next in Pt. 4 and the final portion of the Atlanta address, We look at a direct attack upon the civil disobedience message and tactics put forth by W.E.B. DuBois and others.